Coaching and Toyota Lean

Coaching is becoming widespread in our organizations with many people claiming to be coaches, but with very different interests and skills. To those implementing lean management it is important to recognize that every manager at Toyota has a coach or mentor. In most cases these are other managers. This relationship is central to their culture and improvement process.

Every coach is assisting in the learning or change process, but the roles and goals may differ dramatically. The goals of the coach and the client should be in alignment.

The Continuum of Caring

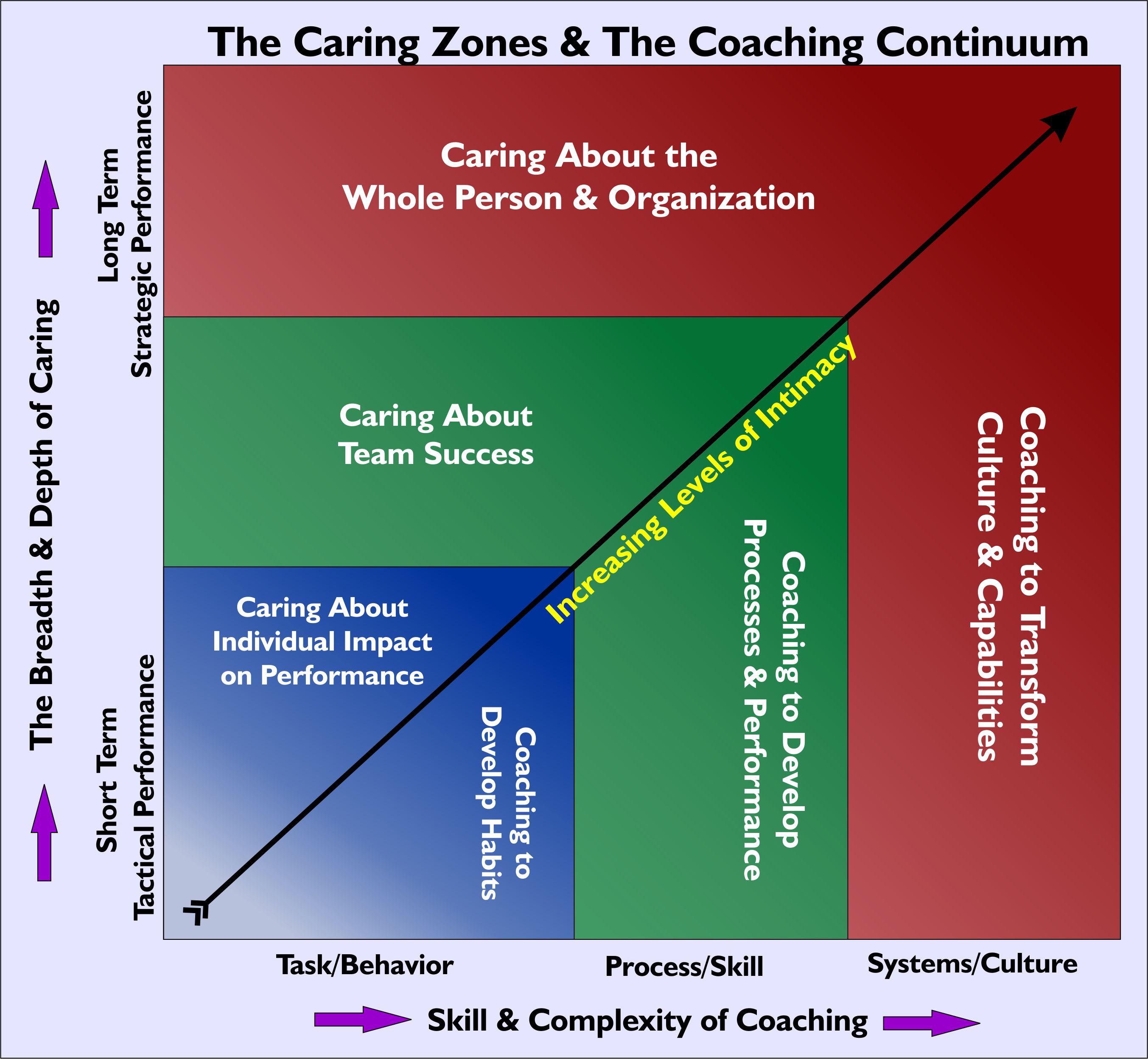

There are numerous ways to describe the continuum of relationships between coach and client: from short-term to long-term, from focused on today’s problems to developing strategic systems and culture, from low to increasing levels intimacy. For the sake of simplicity I will divide this continuum into three zones: the Blue, Green and Red Zones of Caring.

Although you may be operating predominantly in one of these zones along the continuum, they often overlap. They are also additive, not mutually exclusive. If you are a highly skilled coach operating in the Red Zone, you may also function in the Blue and Green Zones in response to the needs of the client.

“Coaching is not so much a methodology as it is a relationship – a particular kind of relationship. Yes, there are skills to learn and a wide variety of tools available, but the real art of effective coaching comes from the coach’s ability to work within the context of relationship.” (Co-Active Coaching, p.15)

Why Caring Matters

If you are a coach, who or what you care about is central to your ability to affect change. Those who are trained in counseling or coaching understand that the relationship between the coach and client is based on trust and trust is established by demonstrating caring or empathy for the client. The degree to which I feel that you care about “me” and “my” success determines the degree to which I am likely to share my own concerns and follow your advice. If the focus of the coach is outside of the client, the needs of someone else, there is little reason to expect the client to accept responsibility for self-reflection or change.

Relationships are highly intuitive and based on far more than the simple words spoken or questions asked. Clients have an intuitive sense of the motivation of the coach. A coach without self-awareness of his or her own motivations is not likely to build a trusting relationship with the client.

1. The Blue Zone: Individual Habits

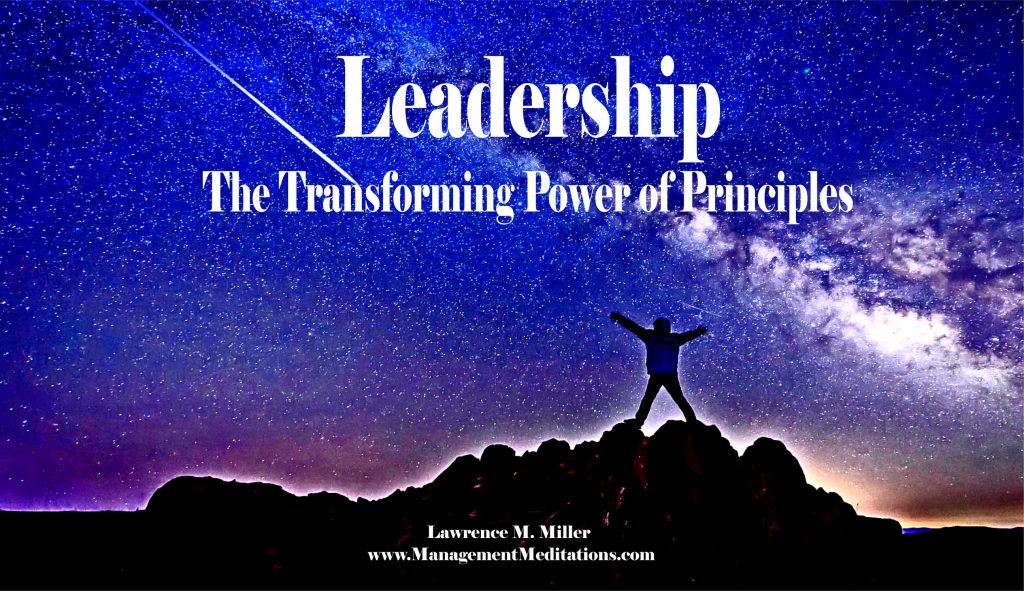

Mike Rother’s book Toyota Kata presents his understanding of both the improvement process and coaching process at Toyota. The Improvement Kata is based on understanding the current condition and the desired future target conditions. In this presentation the challenge is defined by a higher level of management and the individual defines the current and future condition required to meet that challenge. Progress toward closing the gap is made by successive application of the PDCA (plan-do-check-act) cycle of problem solving.

The Coaching Kata is based on the coach repeatedly asking five scripted questions. These questions ask about the current condition, the desired future condition, obstacles to improvement, actions being taken to close the gap, the results of prior actions, and what learning has occurred from those actions. The purpose is both to improve current performance, but also to develop the basic habits of looking at the facts and problem solving. These habits are fundamental to the scientific method of learning through experimentation.

While I fully appreciate the value of repetition and building fundamental habits to improve performance (see my description of this zone of coaching), I am equally convinced that one would be misled to consider this a full understanding of a coaching relationship. While developing these habits does contribute to culture change, there are many other drivers of the culture not addressed by this method.

There are a couple obvious limitations to Blue Zone coaching. First, it demonstrate a superficial caring for the individual client. It is not about the person, but about habits of improving performance. The focus is on the “object” of performance, not the complexity of the person or organization culture. There is a top down assumption that the challenge is set at a higher level of management, assuring that it is not “your” needs, but the needs of the organization that are being addressed. By definition then, it is not about what is important to the client, but what is important to someone else. The focus is also on improving short term performance and not the nature of the organization’s structures, systems, and capabilities that will ultimately determine long-term performance.

From my conversation with Toyota insiders, the reality of Toyota’s coaching process is neither as mechanically repetitious nor as focused on top down challenges as this model suggests. In addition to the five kata questions there are deeper questions asked about the development of people. Rather, it does take into account the other zones of caring dealing with the dedications, motivations, personal leadership, etc.

2. The Green Zone: Teams and Processes

Every family therapist has experienced Mom or Dad bring Johnny to therapy because there is something wrong with him. Johnny is misbehaving, he is broken, please fix him! It doesn’t take long for the therapist to discover that Johnny’s behavior is perfectly rational given the system in which he lives. We all adapt to the system in which we live and a crazy system produces crazy behavior as viewed by an outsider. You can’t fix Johnny without fixing the family system, the behavior of Mom and Dad. If you have watched the Dog Whisperer (Cesar911), you have seen an owner bring their wonderful pooch, who may be attacking everyone who comes in the door, to be fixed. It doesn’t take long for Cesar to recognize that the problem is less the dog than the owners. He focuses more on changing their behavior than that of the dog.

In every organization there is a family system, the first learning organization, the group of people on whom we depend the most and who depend on us. It is the group to which we belong, the team, whether the senior management team or the front line team doing the value adding work. The functioning of this team is the key to the functioning of the entire organization. You can’t improve the performance of the organization without improving the behavior and norms of the natural work and leadership teams.

There is some confusion about the nature of work teams. There is no such thing as a totally self-directed or self-managing work team. The senior management team is directed by the owners of the organization and every team below receives direction and operates within boundaries determined at the level above. However, teams may still be empowered and self-directed within those boundaries. The nature of self-direction, the team’s boundaries, is entirely dependent on the context, the nature of work done by those teams as well as their training and leadership.

Coaching these teams requires a different set of skills and a different relationship than coaching individuals to improve immediate performance. It requires observing patterns of group behavior, helping to define roles and responsibilities, and it is here that the problem solving skills and process mapping are most useful. It is the team kata (discipline of practice) more than the individual kata that will determine both the culture and the performance of the organization.

Coaching teams requires a deep understanding of facilitation skills and group dynamics. It also requires the ability to give feedback to a number of different levels of leaders in the organization.

The team is the transition structure between the individual and the culture of the organization and the coach must now demonstrate caring not only for the individual but for the team as a whole, the family unit. She must observe and give feedback to the entire team. And, rather than the five repetitive questions of the Toyota Kata, she needs to move the team and its leaders up a skills hierarchy. The skills of team leadership are more complex than the Kata questions address. I have attempted to provide a definition of the skills, the actions, and the coaching questions in my Team Kata Coaching Map. This is one way of addressing this complexity.

3. The Red Zone: Transforming People and Culture

Great athletic coaches, particularly at the high school and college level, are not only concerned with the specific skills that lead to success on the field or court. Duke University’s legendary basketball coach, Coach K (Mike Krzyzewski), always talks about the importance of developing his players as “men”, as well functioning human beings, both on and off the court. He has won the NCAA Championship five times, including this year. His focus on the whole person does not diminish his success at teaching the fundamentals of basketball.

The ongoing relationship between coach and client exists only to address the goals of the client – and so naturally, the client’s life is the focus. (Co-Active Coaching, p8,)

The Red Zone has two dimensions, one is the personal concern for the development of the individual and the second is an understanding of the whole-system of the organization. Coaching to improve each of these require both a mental framework and a set of facilitation skills.

The following section on Helping and Human Relations provides a guide to the skills of coaching individuals with regard to their development as whole persons.

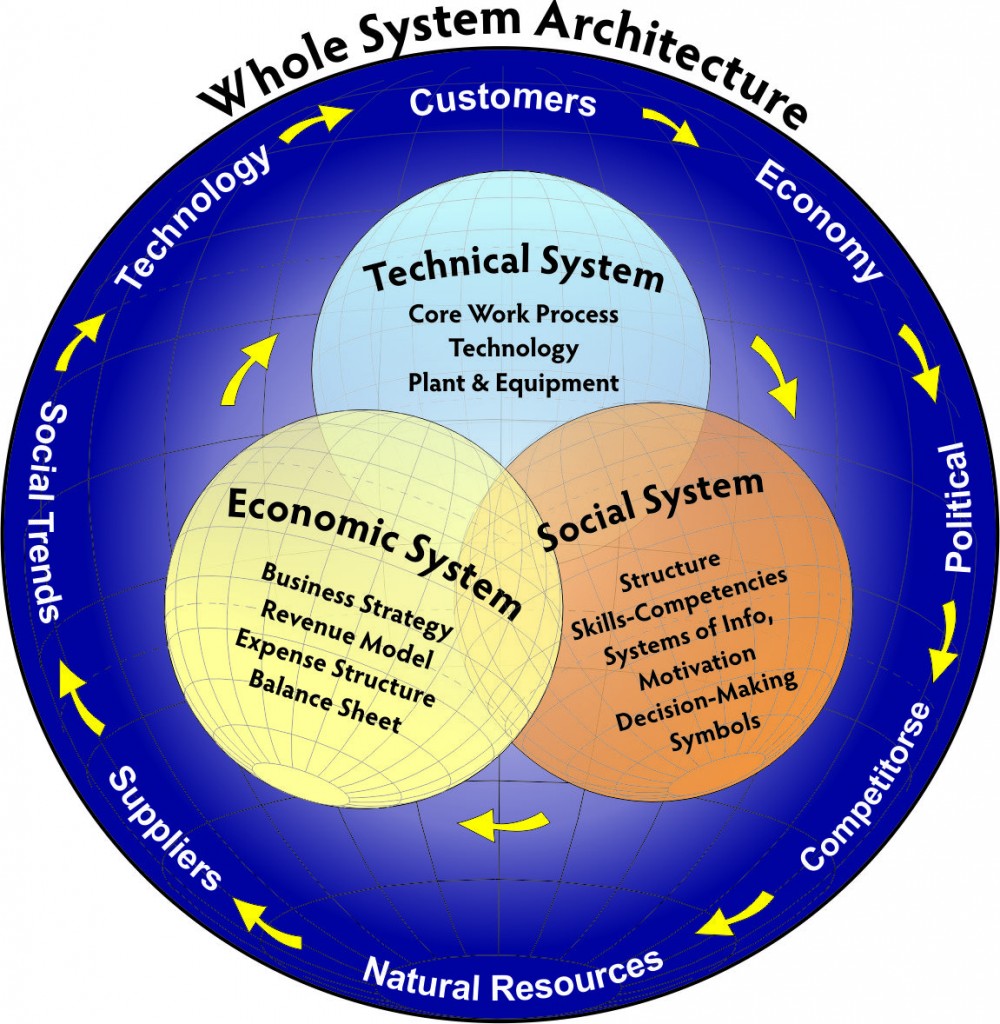

Addressing the organization as a whole-system requires a different set of skills and a different model of change. Socio-technical systems design, or what I have called Whole-System Architecture, provides a conceptual framework and a process of change, which I have detailed in my Getting to Lean book. Of course there are other frameworks that can be employed. However, the framework must address the systems of the organization such as who gets what information, who makes what decisions, how does the structure support the flow of the work, and whether our capabilities match the changing requirements presented by the external landscape.

Addressing the organization as a whole-system requires a different set of skills and a different model of change. Socio-technical systems design, or what I have called Whole-System Architecture, provides a conceptual framework and a process of change, which I have detailed in my Getting to Lean book. Of course there are other frameworks that can be employed. However, the framework must address the systems of the organization such as who gets what information, who makes what decisions, how does the structure support the flow of the work, and whether our capabilities match the changing requirements presented by the external landscape.

The nature of this process and these questions are entirely different from those that address individual habits or the patterns of team behavior. They are analogous to a nation’s tax laws and system of investment and spending, versus a local community’s governance. Too many change efforts that are presented as efforts to change the culture fail to address the systems and structures that reinforce the existing culture and which determine the capabilities of the organization.

Helping and Human Relationship Skills

Early in my career, almost by accident, I found my self as the single counselor for 350 young inmates at a North Carolina prison and with no training in counseling. I acquired Robert R. Carkhuff’s Helping and Human Relations, Volumes 1 and 2. I didn’t know it at the time, but this work of Carkhuff became a classic in the field of counseling.

Carkhuff identified seven major skills that a helper should have to successfully serve a client. It is worth reviewing these characteristics and ask yourself whether or not you demonstrate these skills. Carkhuff used the term “counselor” in the following, which I have replaced with “coach.”

The coach is a person who is living effectively himself or herself and who discloses himself in a genuine and constructive fashion in his response to others. She communicates an accurate empathic understanding and a respect for all of the feelings of the other person and guides discussions with those persons into specific feelings and experiences.

Empathy: The ultimate purpose of the empathic response is to communicate to the client a depth of understanding of her predicament in such a manner that she can expand and clarify her own self-understanding as well as his understanding of others. The guidelines for empathy are:

- The helper concentrates with intensity upon the client’s expressions, verbal and non- verbal.

- The coach concentrates upon responses that are interchangeable with those of the client.

- The coach formulates his responses in language that is most attuned to the client.

- The coach responds in a feeling tone similar to that communicated by the client.

- The coach is most effective in communicating empathic understanding when he is most responsive.

- The coach moves tentatively toward expanding and clarifying the client’s experiences at higher levels.

- The coach concentrates upon what is not being said.

Respect: The communication of respect to the client has several purposes:

- To establish a relationship based upon trust and confidence in which the client can explore relevant concerns;

- To establish a basis on which the client can come to respect herself in areas relevant to his effective functioning;

- To establish a modality through which the client can, with appropriate discriminations, come to respect others in areas relevant to his own functioning. The guidelines for the communication of respect are as follows:

- The coach suspends all critical judgments concerning the client.

- The coach communicates to the client in at least minimally warm and modulated tones.

- The coach concentrates upon understanding the client.

- The coach gives the client the opportunity to make himself known in ways that might elicit positive regard from the coach.

- The coach communicates in a genuine and spontaneous manner.

Concreteness: The communication of concreteness enables the client to deal specifically with all areas of personally relevant concern. The guidelines for the communication of concreteness are:

- The coach makes concrete his own reflections and interpretations.

- The coach emphasizes the personal relevance of the client’s communications.

- The coach asks for specific details and specific instances. The coach relies upon his own experiences as a guideline for determining whether concreteness is appropriate or not.

Genuineness and Self-Disclosure: Genuineness provides both the goal of helping and the necessary contextual base within which helping takes place. The dimension of self-disclosure serves a complementary role to genuineness. The guidelines for communication of these dimensions are as follows:

- The coach attempts to minimize the effects of his role, professional or otherwise.

- The coach communicates no inauthentic responses while she demonstrates an openness to authentic ones.

- The coach increasingly attempts to be as open and free within the helping relationship as is possible.

- The coach can share experiences with the client as fully as possible,

- The coach can learn to make open-ended inquiries into the most difficult areas of his experience.

- The coach relies upon his experiences as the best guideline.

Confrontation: In order to enable the client to confront herself effectively when appropriate, the coach must confront the client for the following discrepancies in her own behavior: discrepancies between the client’s expression of who or what she wishes to be and how she actually experiences herself or how others experience her. The following guidelines may be employed in formulating confrontation responses:

- The coach concentrates upon the client’s expressions, both verbal and non-verbal.

- The coach concentrates initially upon raising questions concerning discrepant communications from the client.

- The coach focuses

Immediacy: With regard to interpretation of the immediacy of the relationship, the key question is, “‘what is the client really trying to tell me that he cannot directly tell me?” The guidelines for communication of immediacy are as follows:

- The coach concentrates on his own personal experience in the immediate moment

- The coach temporarily disregards for the moment the content of the client’s expression.

- The coach employs the frustrating, directionless moments of helping to search the question of immediacy.

- The coach periodically sits back and searches the key question of’ immediacy.

Notes:

- Dr. Jake Abraham, a colleague at Lean Leadership Institute – former TPS manager and trainer of leaders at Toyota – provided input regarding the coaching model.

- The following two books are excellent resources for coaches:

- Co-Active Coaching – Changing Business, Transforming Lives: Henry Kimsey-House, et al, 2011, Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

- Coaching for Leadership: Marshall Goldsmith and Laurence Lyons, 2006, Pfeiffer.